Benjamin Rush

| Benjamin Rush | |

|---|---|

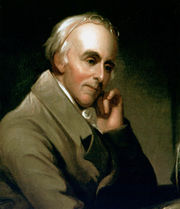

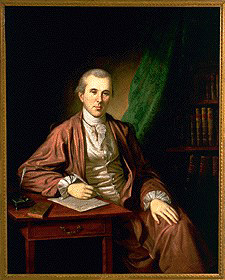

Dr. Benjamin Rush, painted by Charles Willson Peale, c. 1818 |

|

| Born | January 4, 1746 Byberry, Philadelphia County |

| Died | April 19, 1813 (aged 67) Philadelphia, Pennsylvania |

| Occupation | physician, writer, educator |

| Known for | signer of the United States Declaration of Independence |

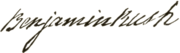

| Signature | |

|

|

Benjamin Rush (January 4, 1746 [O.S. December 24, 1745] – April 19, 1813) was a Founding Father of the United States. Rush lived in the state of Pennsylvania and was a physician, writer, educator, humanitarian and a Universalist,[1] as well as the founder of Dickinson College in Carlisle, Pennsylvania.

Rush was a signatory of the Declaration of Independence and attended the Continental Congress. He was also a staunch opponent of Gen. George Washington and worked tirelessly to have him removed as the Commander-In-Chief of the Continental Army.[2] Later in life, he became a professor of medical theory and clinical practice at the University of Pennsylvania. Despite having a wide influence on the development of American government, he is not as widely known as many of his American contemporaries. Rush was also an early opponent of slavery and capital punishment.

Despite his great contributions to early American society, Rush may be more famous today as the man who, in 1812, helped reconcile the friendship of Thomas Jefferson and John Adams by encouraging the two former Presidents to resume writing to each other.[3][4]

Contents |

Life

Rush was born to John Rush and Susanna Hall in the Township of Byberry in Philadelphia County, which was then about 14 miles outside Philadelphia (the township was incorporated into Philadelphia in 1854 and now remains one of its neighborhoods). His father died when he was six, and he spent most of his early life with his maternal uncle, the Reverend Samuel Finley. He attended Finley's academy at Nottingham, which would later become West Nottingham Academy.

In 1760, at age 15, he completed the five-year program earning him a Bachelor of Arts degree at the College of New Jersey (now Princeton University) and then studied medicine under Dr. John Redman in Philadelphia. Redman encouraged him to further his studies at the University of Edinburgh, where he earned a medical degree. While in the United Kingdom practicing medicine, he learned French, Italian, and Spanish. Returning to the Colonies in 1769 (age 24), Rush opened a medical practice in Philadelphia and became Professor of Chemistry at the College of Philadelphia (now the University of Pennsylvania).

He published the first American textbook on chemistry, several volumes on medical student education, and wrote influential patriotic essays. He was active in the Sons of Liberty and was elected to attend the provincial conference to send delegates to the Continental Congress. He was consulted by Thomas Paine on the writing of the profoundly influential pro-independence pamphlet Common Sense. He was appointed to represent Pennsylvania at the Continental Congress and signed the Declaration of Independence.

In 1777 he became surgeon-general of the middle department of the Continental Army. Conflicts with the Army Medical service, specifically with Dr. William Shippen, Jr., led to Rush's resignation in 1778.

Attacks on George Washington

Rush campaigned for the removal of Gen. George Washington early in the Revolutionary War, as part of the secretive Conway Cabal, losing Washington's trust and ending Rush's war activities.

Author Dave R. Palmer wrote this about Rush and his actions:

(He) weighed in with words more poisionous than most, penning a cryptic assessment of "the state of disorders of the American Army." Washington, he claimed, was a puppet in the hands of a few officers at headquarters. The major generals were a sorry lot. The soldiers ragged and undisciplined. There was "bad bread, no order, universal disgust." He also told John Adams that officers referred to Gates' army as "a well-regulated family", but called the forces directly under Washington "an unformed mob." He went on to contrast Gates, at the "pinnacle of military glory", to Washington, who had been "outgeneraled and twice beaten." He was not reticent to share his views with others near and far.[2]

Rush later, after the fact, expressed regret for his actions against Washington. In a letter to John Adams in 1812, Rush wrote, "He [Washington] was the highly favored instrument whose patriotism and name contributed greatly to the establishment of the independence of the United States."

Post Revolution

In 1783 he was appointed to the staff of Pennsylvania Hospital, of which he remained a member until his death.

He was elected to the Pennsylvania convention which adopted the Federal constitution and was appointed treasurer of the U.S. Mint, serving from 1797-1813.

He became Professor of medical theory and clinical practice at the University of Pennsylvania in 1791, though the quality of his medicine was quite primitive even for the time: he advocated bleeding (for almost any illness) long after its practice had declined. He became a social activist, an abolitionist, and was the most well-known physician in America at the time of his death. He was also founder of the private liberal arts college Dickinson College, in Carlisle, Pennsylvania. In 1794, he was elected a foreign member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences.

Rush was a founding member of the Philadelphia Society for Alleviating the Miseries of Public Prisons (known today as the Pennsylvania Prison Society[5]), which greatly influenced the construction of Eastern State Penitentiary in Philadelphia.

Corps of discovery

In 1803, Thomas Jefferson sent Meriwether Lewis to Philadelphia to prepare for the Lewis and Clark Expedition under the tutelage of Rush, who taught Lewis about frontier illnesses and the performance of bloodletting. Rush provided the corps with a medical kit that included:

- Turkish opium for nervousness

- emetics to induce vomiting

- medicinal wine

- fifty dozen of Dr. Rush's Bilious Pills, laxatives containing more than 50% mercury, which the corps called "thunderclappers". Their meat-rich diet and lack of clean water during the expedition gave the men cause to use them frequently. Though their efficacy is questionable, their high mercury content provided an excellent tracer by which archaeologists have been able to track the corps' actual route to the Pacific.

Abolitionism

In 1766 when Rush set out for his studies in Edinburgh, was outraged by the sight of 100 slave ships in Liverpool harbor.[6] As a prominent Presbyterian doctor and professor of chemistry in Philadelphia, he provided a bold and respected voice against the slave trade that could not be ignored.

The highlight of his involvement in abolishing slavery might be the pamphlet he wrote that appeared in Philadelphia, Boston, and New York in 1773 entitled "An Address to the Inhabitants of the British Settlements in America, upon Slave-Keeping." In this first of his many attacks on the social evils of his day, he not only assailed the slave trade, but the entire institution of slavery. Dr. Rush argued scientifically that Negroes were not by nature intellectually or morally inferior. Any apparent evidence to the contrary was only the perverted expression of slavery, which "is so foreign to the human mind, that the moral faculties, as well as those of the understanding are debased, and rendered torpid by it."

"In 1792 Dr Benjamin Rush, one of the 'Founding Fathers' of the USA, presented a paper before the American Philosophical Society which argued that the 'color' and 'figure' of blacks were derived from a form of leprosy. He was convinced that with proper treatment, blacks could be cured (i.e. become white) and eventually... assimilated into the general population" (Omi & Winant 1986: 148). Omi, M. and H. Winant (1986). Racial formation in the United States : from the 1960s to the 1980s. New York ; London, Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Contributions to medicine

Although anatomy was well understood in Rush's time, the causes of disease remained elusive. Doctors therefore relied on various unscientific treatments. Although Rush continued these practices, he actively sought new explanations and new approaches to treatment, some of which remain influential.

Physical medicine

Rush was a proponent of bloodletting[7] and calomel therapy, treatments that were widespread in America at the time. In his report on the Philadelphia yellow fever epidemic, he wrote:

- I have found bleeding to be useful, not only in cases where the pulse was full and quick, but where it was slow and tense. I have bled twice in many, and in one acute case four times, with the happiest effect. I consider intrepidity in the use of the lancet, at present, to be necessary, as it is in the use of mercury and jalap, in this insidious and ferocious disease.

Some contemporaries, notably William Cobbett, objected to Rush's extreme use of bloodletting. Cobbett accused Rush of killing more patients than he had saved. Rush sued Cobbett for libel, winning a judgment of $500.[8]

Rush reviewed the case of Henry Moss, a slave who lost his dark skin color (probably through vitiligo). He proposed that being black was a hereditary skin disease, which he called "negroidism," and that it might be cured. Rush drew the conclusion that "Whites should not tyrannize over [blacks], for their disease should entitle them to a double portion of humanity. However, by the same token, whites should not intermarry with them, for this would tend to infect posterity with the 'disorder'... attempts must be made to cure the disease."[9]

Rush wrote a descriptive account of the yellow fever epidemic that struck Philadelphia in 1793 (during which he treated up to 120 patients per day), and what is considered to be the first case report on dengue fever (published in 1789 on a case from 1780).

Mental health

Rush was far ahead of his time in the treatment of mental illness. In fact, he is considered the "Father of American Psychiatry", publishing the first textbook on the subject in the United States, Medical Inquiries and Observations upon the Diseases of the Mind (1812).[10] He undertook to classify different forms of mental illness and to theorize as to their causes and possible cures. Rush believed (incorrectly) that many mental illnesses were caused by disruptions of the blood circulation, and treated them with devices meant to improve circulation to the brain such as a restraining chair and a centrifugal spinning board.[11] After seeing mental patients in appalling conditions in the Pennsylvania Hospital, Rush led a successful campaign in 1792 for the state to build a separate mental ward where the patients could be kept in more humane conditions.[12]

Rush is sometimes considered a pioneer of occupational therapy particularly as it pertains to the institutionalized.[13] In Diseases of the Mind Rush wrote:

- "It has been remarked, that the maniacs of the male sex in all hospitals, who assist in cutting wood, making fires, and digging in a garden, and the females who are employed in washing, ironing, and scrubbing floors, often recover, while persons, whose rank exempts them from performing such services, languish away their lives within the walls of the hospital".

Furthermore, Rush was one of the first people to describe Savant Syndrome. In 1789 he described the abilities of Thomas Fuller, a lightning calculator. His observation would later be described in other individuals by notable scientists like John Langdon Down.[14]

Rush pioneered the therapeutic approach to addiction.[15][16] Prior to his work, drunkenness was viewed as being sinful and a matter of choice. Rush believed that the alcoholic loses control over himself and identified the properties of alcohol, rather than the alcoholic's choice, as the causal agent. He developed the conception of alcoholism as a form of medical disease and proposed that alcoholics should be weaned from their addiction via less potent substances.[17]

Education

During his career, he educated over 3000 medical students, and several of these established Rush Medical College (Chicago) in his honor after his death. One of his last apprentices was Samuel A. Cartwright, later a Confederate States of America surgeon charged with improving sanitary conditions in the camps around Vicksburg, Mississippi, and Port Hudson, Louisiana. Rush University Medical Center in Chicago, formerly Rush-Presbyterian-St. Luke’s Medical Center, was named in his honor.

Religious views and vision

He is generally deemed Presbyterian and was a founder of the Philadelphia Bible Society.[18] He was an advocate for Christianity in public life and in education. In line with that, he advocated that the U.S. government require public schools to teach students using the Bible as a textbook, that the government furnish an American bible to every family at public expense and that "the following sentence be inscribed in letters of gold over the door of every State and Court house in the United States. The Son of Man Came into the World, Not To Destroy Men's Lives, But To Save Them." [19][20][21] He publicly advocated such government actions even after the ratification in 1791 of the First Amendment to the United States Constitution, which states: "Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof;...."[22]

His religious views were influenced around 1780 by what he described as "Fletcher's controversy with the Calvinists in favor of the Universality of the atonement." After hearing Elhanan Winchester preach, Rush indicated that Winchester's theology "embraced and reconciled my ancient calvinistical, and my newly adopted (Arminian) principles. From that time on I have never doubted upon the subject of the salvation of all men." Rush did believe, as did Winchester and most Universalists, in a state of punishment after death for the wicked.

In his later years, Rush, in a letter to John Adams, described his religious views as "a compound of the orthodoxy and heterodoxy of most of our Christian churches."[23]

He also helped Richard Allen in the founding of the African Methodist Episcopal Church.

Family

Benjamin Rush's great-great-grandfather, John Rush, came with his wife, Susannah (Lucas) Rush from England in 1683. Susannah Lucas was first cousin to William Penn who established Pennsylvania. Their mothers were sisters. Before the Revolutionary war, Rush was engaged to Sarah Eve, daughter of prominent Philadelphian, Captain Oswell Eve, Sr. Their wedding date was set for mid-December 1774. Unfortunately, Sarah became ill and died on 4 Dec 1774, 2 weeks before their intended date.

Rush married Julia Stockton (1759–1848) (daughter of Richard Stockton, another signer of the Declaration of Independence, and his wife Annis Boudinot Stockton) on 11 Jan 1776. They had 13 children, 9 of whom survived their first year. Benjamin & Julia had: John, Ann Emily, Richard, Susannah (died as infant), Elizabeth Graeme (died as infant), Mary B, James, William (died as an infant), Benjamin (died as an infant), Benjamin, Julia, Samuel, William.

Ann Emily married the Honorable Ross Cuthbert; Richard Rush became an attorney and married Catherine Elizabeth Murray; Mary married Major Thomas Manners; James became a medical doctor and married Eugenia Frances Heister and Elizabeth Upshur Dennis; Benjamin did not marry, moved to New Orleans, LA; Julia married Henry Jonathon Williams Esquire; Samuel became an attorney and married Nancy Anne Wilmer; William became a doctor and married Elizabeth Fox Roberts.

Rush's eldest son, John, initially followed his father into medicine, then joined the navy. During his tour, a friend and fellow officer challenged him to a duel. John shot and killed the challenger and was soon consumed by feelings of guilt. When he returned home unable to care for himself, Rush placed him in the mental ward at the Pennsylvania Hospital, where he died 30 years later without having recovered.[24]

Writings

- Letters of Benjamin Rush, volume 1: 1761-1792 (1951), editor L.H. Butterfield, Princeton University Press

- Essays: Literary, Moral, and Philosophical (1798) Philadelphia: Thomas & Samuel F. Bradford, 1989 reprint: Syracuse University Press, ISBN 0-912756-22-5, includes "A Plan of a Peace-Office for the United States"

- The Autobiography of Benjamin Rush: His "Travels Through Life" Together with his Commonplace Book for 1789-1813, 1970 reprint: Greenwood Press, ISBN 0-83713037-9

- Medical Inquiries And Observations Upon The Diseases Of The Mind, 2006 reprint: Kessinger Publishing, ISBN 1-42862669-7

- The Spur of Fame: Dialogues of John Adams and Benjamin Rush, 1805-1813 (2001), Liberty Fund, ISBN 0-86597287-7

- Benjamin Rush, M.D: A Bibliographic Guide (1996), Greenwood Press, ISBN 0-31329823-8

- An Address to the Inhabitants of the British Settlements in America, Upon Slave-keeping. Philadelphia: Printed by J. Dunlap, 1773.

Buried

He is buried in the Christ Church Burial Ground in Philadelphia, not far from where Benjamin Franklin is buried.

Notes

- ↑ "Benjamin Rush". UNitarian Universalist Association. 2010-07-08. http://www25.uua.org/uuhs/duub/articles/benjaminrush.html. Retrieved 2010-07-08.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 George Washington and Benedict Arnold. Regnery. 2006. pp. 264–265, 282.

- ↑ ""Two Pieces of Homespun" (Memory): American Treasures of the Library of Congress". The Library of Congress. 2002-11-22. http://www.loc.gov/exhibits/treasures/trm136.html. Retrieved 2008-02-24.

- ↑ McCullough, David (2001). John Adams. Simon and Schuster. pp. 599–603. ISBN 0684813637.

- ↑ "The Prison Society – About Us". The Pennsylvania Prison Society. http://www.prisonsociety.org/about/index.shtml. Retrieved 2008-11-16.

- ↑ "Dr. Benjamin Rush and the Negro", Donald J. D'Elia, Journal of the History of Ideas, Vol. 30, No. 3 (Jul. - Sep., 1969), pp. 413-422, doi:10.2307/2708566 University of Pennsylvania Press

- ↑ Rush, Benjamin (1815). "A Defence of Blood-letting, as a Remedy for Certain Diseases". Medical Inquiries and Observations 4. http://www.oocities.com/bobarnebeck/defence.html. Retrieved 2008-05-15.

- ↑ Fruchtman, Jack (2005). Atlantic Cousins: Benjamin Franklin and His Visionary Friends. New York: Thunder's Mouth Press.

- ↑ Rush, Benjamin (1799). "Observations Intended to Favour a Supposition That the Black Color (As It Is Called) of the Negroes Is Derived from the Leprosy". Transactions of the American Philosophical Society 4.

- ↑ Hellemans, Alexander; Bryan Bunch (1988). The Timetables of Science. New York, New York: Simon and Schuster. pp. 261. ISBN 0671621300.

- ↑ Beam, Alex (2001). Gracefully Insane: Life and Death Inside America's Premier Mental Hospital.

- ↑ Deutsch, Albert (2007). The Mentally Ill in America: A History of Their Care and Treatment From Colonial Times.

- ↑ Brodsky, Alyn (2004). Benjamin Rush: Patriot and Physician.

- ↑ http://www.wisconsinmedicalsociety.org/savant_syndrome/overview_of_savant_syndrome/synopsis

- ↑ Elster, Jon (1999). Strong Feelings: Emotion, Addiction, and Human Behavior. MIT Press. pp. 131. ISBN 0262550369. http://books.google.com/?id=63_19D3jPDgC&pg=PA131&lpg=PA131&dq=%22benjamin+rush%22+%22harry+levine%22.

- ↑ Durrant, Russil; Jo Thakker (2003). Substance Use & Abuse: Cultural and Historical Perspectives. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- ↑ Rush, Benjamin (1805). Inquiry into the Effects of Ardent Spirits upon the Human Body and Mind. Philadelphia: Bartam.

- ↑ Benjamin Rush, Signer of Declaration of Independence

- ↑ "Signers of the Declaration (Benjamin Rush)". U. S. National Park Service. http://www.nps.gov/history/history/online_books/declaration/bio42.htm. Retrieved 2007-12-13.

- ↑ Rush, Benjamin, M.D. (1806). "A plan of a Peace-Office for the United States". Essays, Literary, Moral and Philosophical. (2nd ed.). Thomas and William Bradford, Philadelphia. pp. 183–188. http://books.google.com/?id=xtUKAAAAIAAJ&pg=PA183&dq=benjamin+rush+peace+plan+office#v=onepage&q=. Retrieved 2010-06-03.

- ↑ A Plan of a Peace-Office for the United States in Runes, Dagobert D., The Selected Writings of Benjamin Rush, Philosphical Library, New York, p. 19. Published by READ BOOKS, 2008 ISBN 1443731080 in Google Books Accessed April 27, 2009.

- ↑ Amendment 1 of the United States Constitution in official website of the U.S. National Archives Accessed April 15, 2009.

- ↑ Benjamin Rush. Dictionary of Unitarian and Universalist Biography. Accessed Nov. 25, 2007.

- ↑ Landsman, Ned C. (2001). Nation and Province in the First British Empire. Bucknell University Press.

Sources

- Levine, Harry G. "The Discovery of Addiction: Changing Conceptions of Habitual Drunkenness in America." Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1978; 15: pp: 493-506. Also available at: http://www.soc.qc.cuny.edu/Staff/levine/doa.htm

Further reading

- Brodsky, Alyn. Benjamin Rush: Patriot and Physician. New York: Truman Talley Books/St. Martin's Press, 2004.

- David Freeman Hawke, Benjamin Rush: Revolutionary Gadfly. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, 1971.

- Rush, Benjamin (1947). The selected writings of Benjamin Rush. New York: Philosophical Library. pp. 448. ISBN 978-0806529554.

External links

- Benjamin Rush at the Biographical Directory of the United States Congress

"Rush, Benjamin". Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography. 1900.

"Rush, Benjamin". Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography. 1900.- Article and portrait at "Discovering Lewis & Clark"

- "Benjamin Rush". Find a Grave. http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=915. Retrieved August 11, 2010.

- Benjamin Rush Birthplace at the Historic American Buildings Survey

- Benjamin Rush Birthplace, Springhouse at the Historic American Buildings Survey

|

|||||||